What is a frozen shoulder?

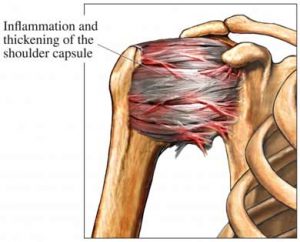

A frozen shoulder, or adhesive capulitis, is a severe restriction of shoulder motion. Adhesions (abnormal bands of tissue) grow between the joint surfaces, restricting motion. There is also a lack of synovial fluid, which normally lubricates the gap between the arm bone and socket to help the shoulder joint move. It is this restricted space between the capsule and ball of the humerus that distinguishes adhesive capsulitis from a less complicated painful, stiff shoulder.

A frozen shoulder, or adhesive capulitis, is a severe restriction of shoulder motion. Adhesions (abnormal bands of tissue) grow between the joint surfaces, restricting motion. There is also a lack of synovial fluid, which normally lubricates the gap between the arm bone and socket to help the shoulder joint move. It is this restricted space between the capsule and ball of the humerus that distinguishes adhesive capsulitis from a less complicated painful, stiff shoulder.

What causes a frozen shoulder?

The cause of frozen shoulder is unknown. However, it is well known that it does not occur in any other joint in the body. The capsule surrounding the shoulder joint thickens and contracts. This leaves less space for the upper arm bone (humerus) to move around. Frozen shoulder can also develop after a prolonged immobilization because of trauma or surgery to the joint. Usually only one shoulder is affected, although in about one-third of cases, motion may be limited in both arms.

Are there risk factors for a frozen shoulder?

- It affects more women than men (70% of the cases occur in women).

Its usual onset begins between ages 40 and 65.

It affects approximately 10% to 20% of diabetics.

Other predisposing factors include:

A period of enforced immobility, resulting from trauma, overuse injuries or surgery.

Hyperthyroidism

Cardiovascular disease

Clinical depression

Parkinson’s disease

How is a frozen shoulder diagnosed?

With a frozen shoulder, the joint becomes so tight and stiff that it is nearly impossible to carry out simple movements, such as raising the arm. People complain that the stiffness and discomfort worsens at night. A doctor may suspect the patient has a frozen shoulder if a physical examination reveals limited shoulder movement, especially internal rotation.

What are the stages of frozen shoulder?

Frozen shoulder develops slowly, and in three stages:

- Stage One: Pain increases with movement and is often worse at night. There is a progressive loss of motion with increasing pain. This stage lasts approximately 2 to 9 months.

- Stage Two: Pain begins to diminish, and moving the arm is more comfortable. However, the range of motion is now much more limited, as much as 50 percent less than in the other arm. This stage may last 4 to 12 months.

- Stage Three: The condition begins to resolve. Most patients experience a gradual restoration of motion over the next 12 to 42 months; surgery may be required to restore motion for some patients.

What is the treatment for a frozen shoulder?

Usually, a frozen shoulder can be treated with an aggressive physical therapy program. The patient begins an intensive passive therapy program that includes supervised physical therapy and a home program that is performed three times a day. Emphasis is placed on forward elevation, external and internal rotation. ; Symptoms are controlled with anti-inflammatories (Advil, ibuprofen, naproxen), pain medication, and corticosteroid injections.

Usually, a frozen shoulder can be treated with an aggressive physical therapy program. The patient begins an intensive passive therapy program that includes supervised physical therapy and a home program that is performed three times a day. Emphasis is placed on forward elevation, external and internal rotation. ; Symptoms are controlled with anti-inflammatories (Advil, ibuprofen, naproxen), pain medication, and corticosteroid injections.

Occasionally, the patient is unable to regain their motion without further treatment. The next method of treatment is usually a manipulation under anesthesia. Essentially, the patient is put to sleep for approximately 5 minutes while a therapy session is performed to regain motion. The patient then wakes up and goes straight to their next physical therapy session (the same day) in order to maintain their motion. In protracted cases of adhesive capsulitis that have failed all other treatments, an arthroscopic capsular release of performed. The results in the literature for this type of surgery are mixed.

How are the overall results for treatment of a frozen shoulder?

Overall, the results of treatment are good. The longer adhesive capsulitis goes untreated, the more difficult recovery is. Approximately 80% of the time, once the frozen shoulder resolves, the underlying cause of the frozen shoulder persists (i.e. rotator cuff tendonitis, AC arthritis) and must then be treated.